History of the Métis in Saskatoon

The dominant historical narrative indicates that Saskatoon was “founded” as a temperance colony by Ontario Protestants in 1882. However, the site of Saskatoon was occupied by the Métis prior to 1882. In 1924, Patrice Fleury, a Métis leader during the 1885 Resistance, recounted assisting in an organized bison hunt in the spring of 1858 in the Saskatoon area. He recalled meeting Gabriel Dumont, then a young man renowned for being a great shot and for being perfectly fearless. The Métis frequently hunted in the bison-feeding grounds of the plains east, west, and south of present-day Saskatoon, where “buffalo grass” was plentiful and the river accessible. The vast herds made these plains a permanent summer pasture.

A 1927 memoir by Archie Brown tells of a bison hunt in what is now Saskatoon, which Gabriel Dumont related to him:

During the first snowfall a party of them (Dumont and his bison-hunting party) were running buffalo on the flats where Saskatoon now stands. He had shot a buffalo and, getting off his horse straddled the buffalo intending to cut its throat. The buffalo rose to its feet and started with him on its back or neck. He soon fell off, however, and the buffalo went a short distance and fell again. He then finished him and he had a ride on a wild buffalo.

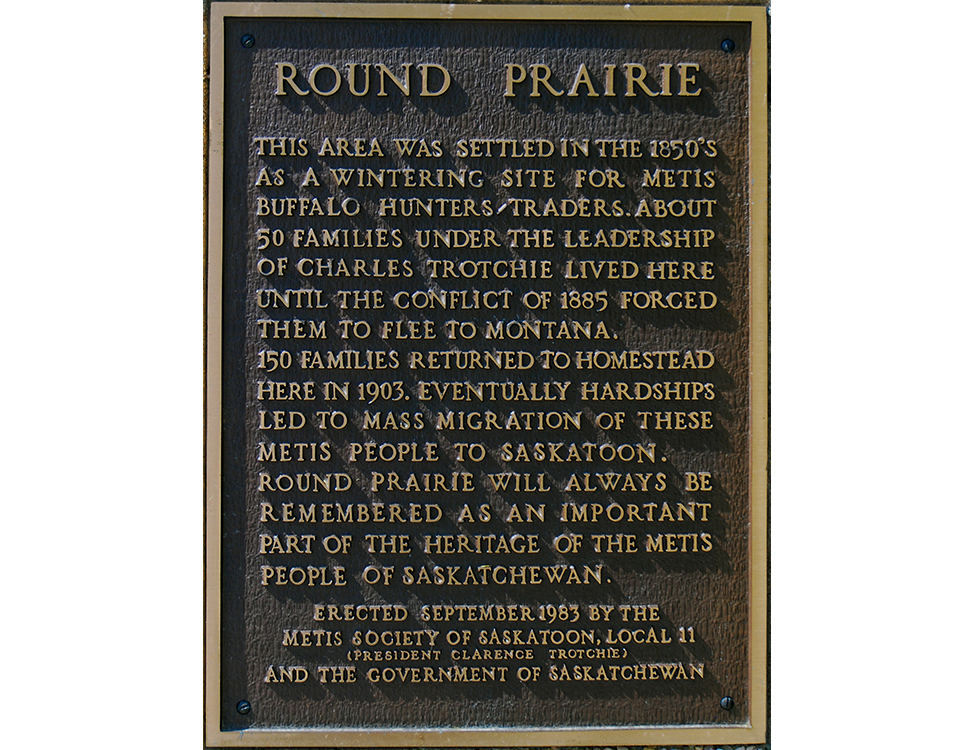

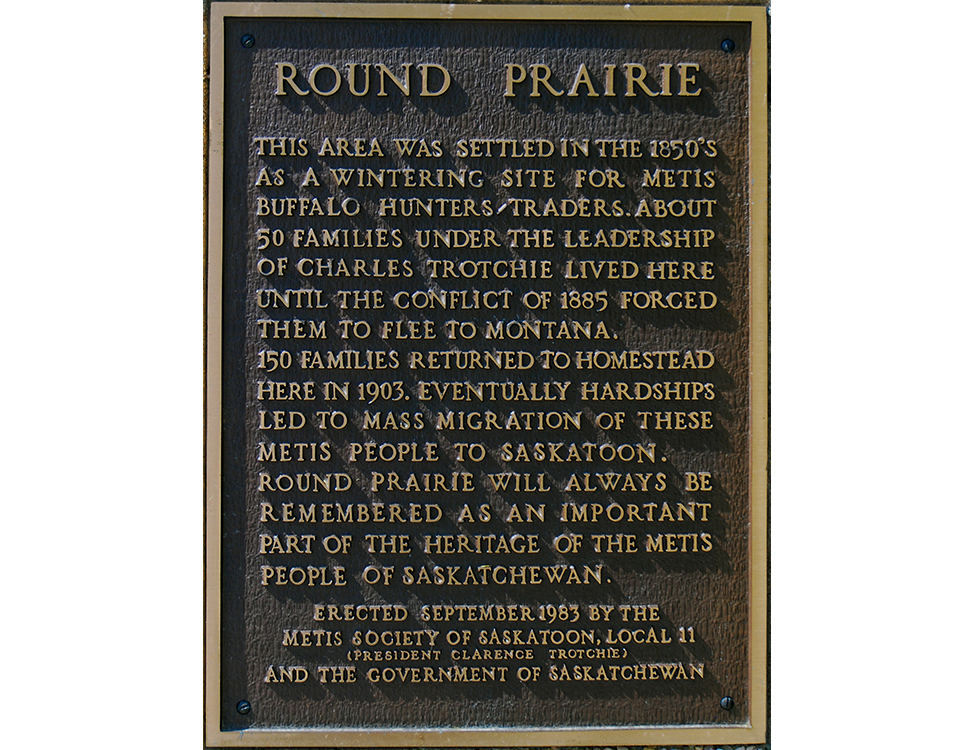

By the 1870s, present-day Saskatoon was part of a larger Métis community that included the Southbranch Settlements (St. Louis, St. Laurent, Batoche, Petite Ville, and Toround’s Coulee or Fish Creek) to the north and the La Prairie Round Settlement (Round Prairie, near Dundurn) to the south. During this time, the Métis also used a Red River cart trail from Batoche to Moose Woods (the present-day Whitecap Dakota First Nation) which went through what is now Saskatoon. Saskatoon also had a Métis name. As late as 1889, Gabriel Dumont called Saskatoon “Bois de flèche” or Arrow Woods. For the Métis, the area in and around Saskatoon was more than a hunting ground, they also had the beginnings of a permanent settlement here. They had riverlots in the Saskatoon region that they wanted to ensure their title to, but the Temperance Society’s leader John Lake worked with the federal government to take this land away from them in the early 1880s.

Before it was incorporated as a city, Saskatoon had a significant Métis presence, including various nearby Road Allowance communities, such as “Frenchmen’s Flats” and Round Prairie. Métis Road Allowance communities, largely residents from Round Prairie, existed in Saskatoon’s Nutana and Exhibition areas well into the 1950s. Members of the Saskatoon Métis community were active in Métis politics and activism from the 1940s, but especially during the 1960s and ‘70s, when they established a number of Métis Society of Saskatchewan Locals and were involved in developing social programs to benefit community members. In 1980, the Gabriel Dumont Institute began operations in Saskatoon, providing the city’s Métis residents with educational, technical, vocational, and cultural programming while establishing a provincial presence to meet its mission. Today, Saskatoon is home to a large vibrant Métis community of over 15,000.

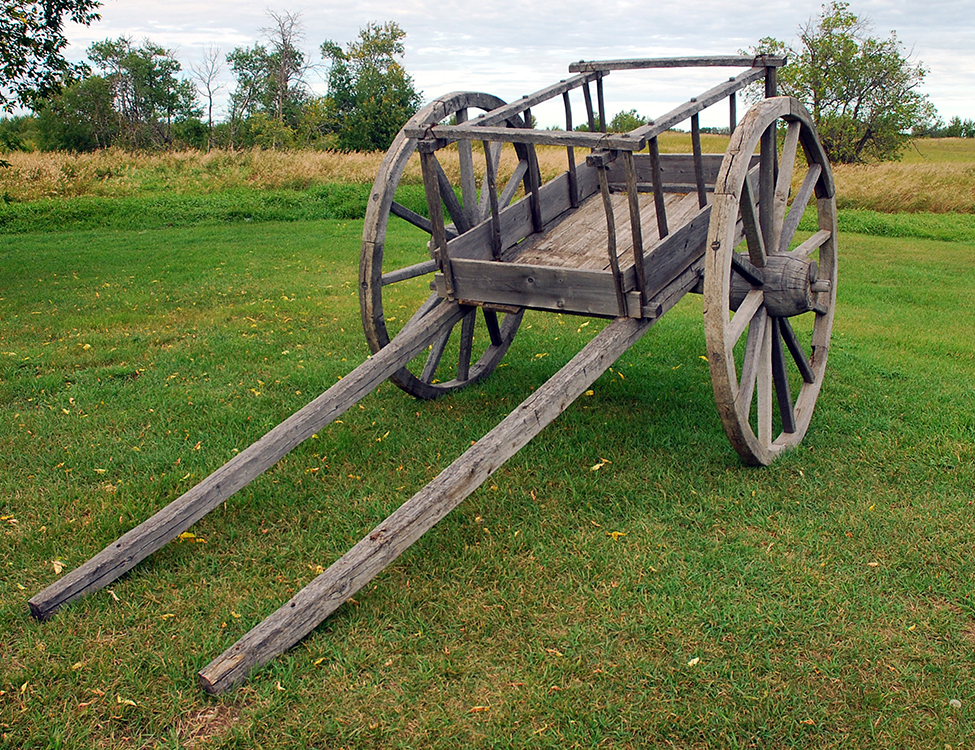

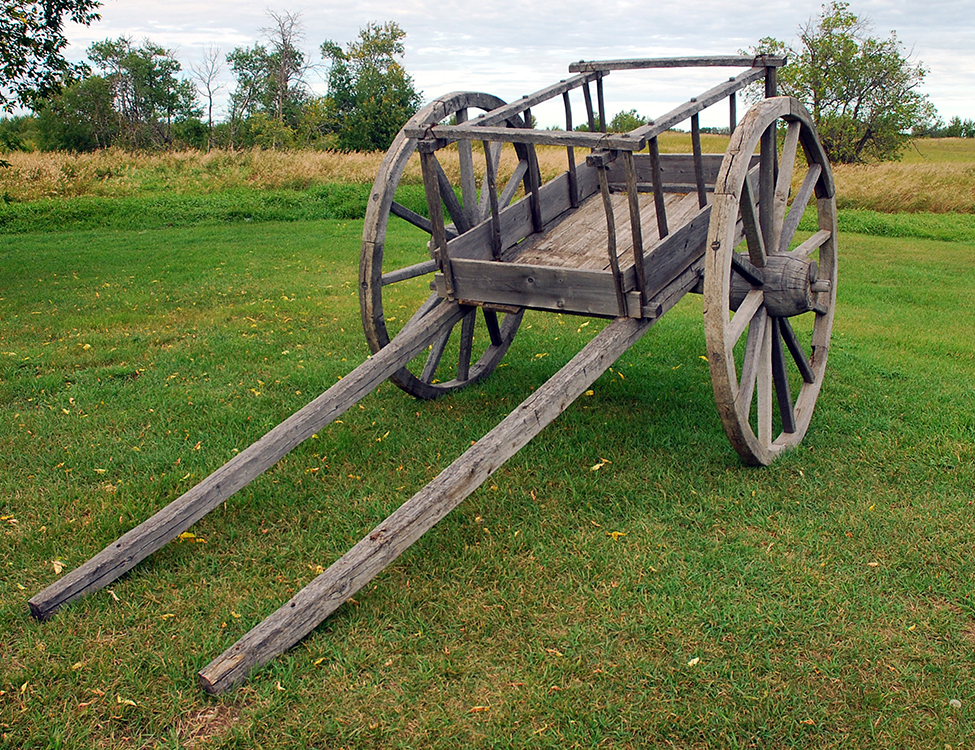

Red River Carts / Lii Shaarets

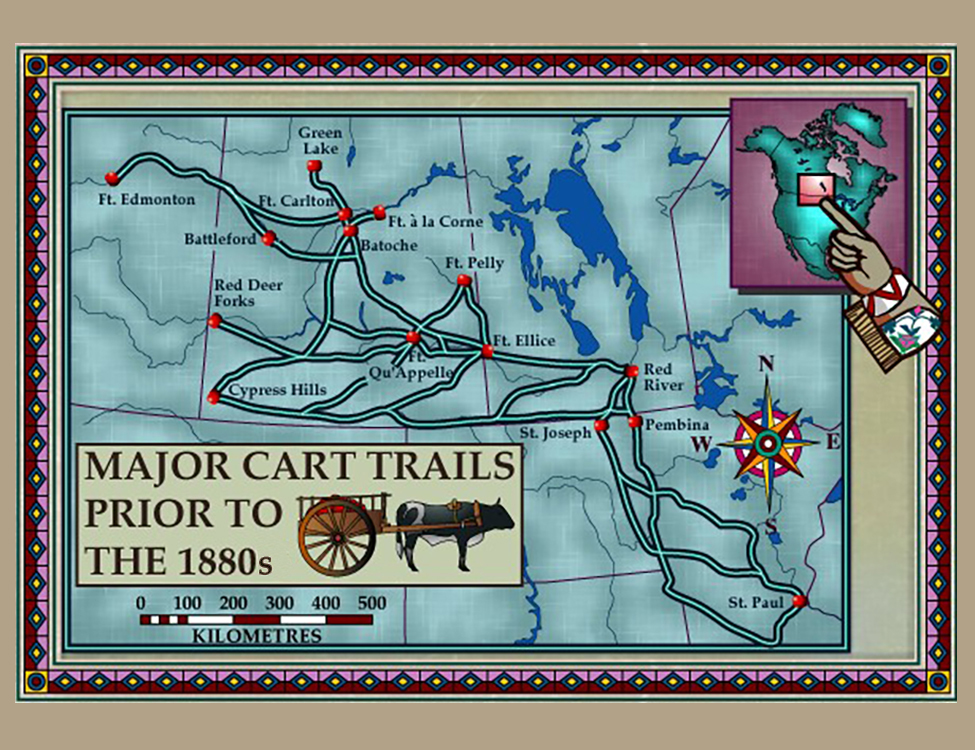

Noisy but versatile, Red River carts crisscrossed what are now the western plains and parkland areas along a series of well-worn trails during much of the nineteenth century. These two-wheeled carts became so identified with the Métis that the Plains First Nations sign language symbol for the Métis literally meant “half-wagon, half-man.” Red River carts could carry 200-500 kilograms of freight and could travel 30-80 kilometres a day, both of which depended on whether they were pulled by a horse or an ox. Oxen could haul more freight but they covered less distance than horses. Organized into long cart trains, Métis traders travelled extensively across the numerous cart trails, which linked settlements together before the coming of the railway and extended beyond the International Boundary to their relatives in communities established beforehand. Many of these Red River cart trails would later become roads and highways in Western Canada.

For the Métis, the Red River cart was an all-purpose utility vehicle and a makeshift home. Being made entirely of wood, any local trees could be used to make repairs. Since Red River carts were made completely from wood, they required no lubrication, which also made them very noisy. Red River carts squealed and squeaked as they traversed the open prairie.

When disassembled, Red River carts became temporary rafts for water crossings. Métis families also used them to move their possessions while travelling to their various territories or for resource harvesting. The carts also provided Métis with temporary living quarters and shelter from the elements and they were used as a defensive mechanism when the Métis were threatened. Inside a circle of carts, women, children, and animals could hide safely, while the men defended them from rifle pits around the carts’ perimeter.

Today, Red River carts are an important Métis symbol, demonstrating the Métis’ freedom, ingenuity, and skill as entrepreneurs.

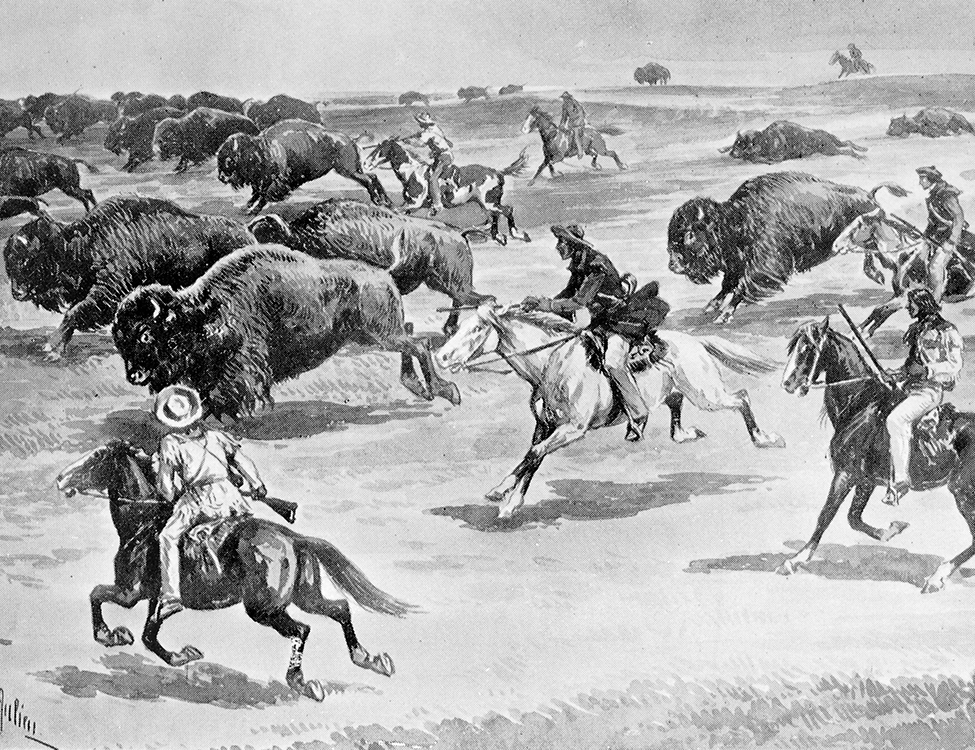

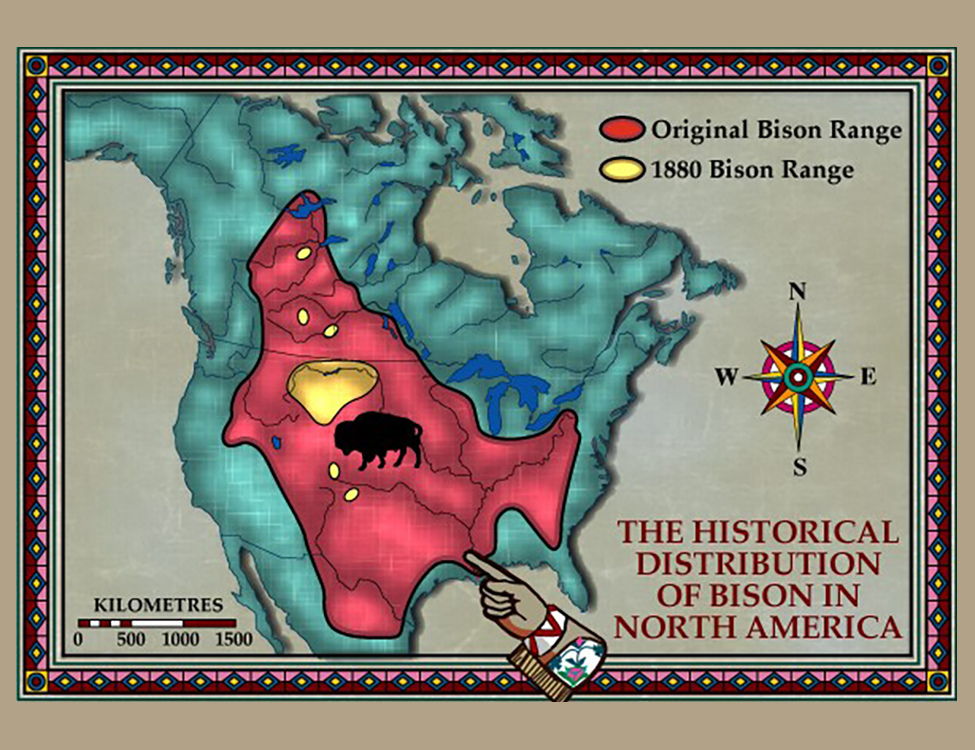

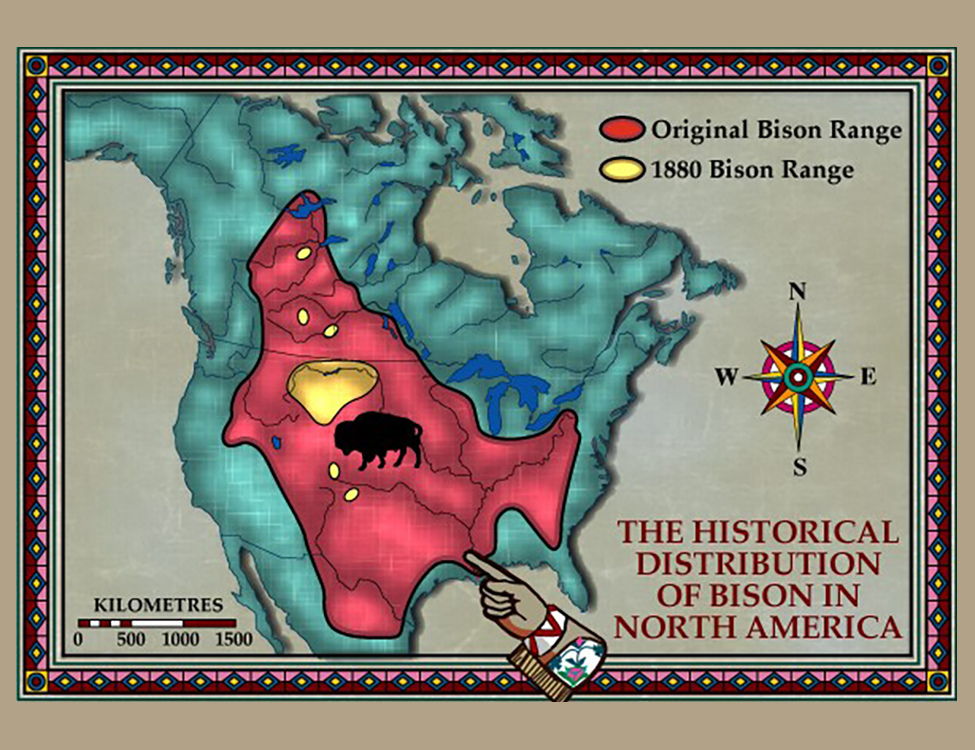

Bison / Lii Buffloo

From the 1810s until the 1870s, Plains bison were the Métis’ main source of survival and income. The Métis went on two major hunts a year: one in the winter and one in the spring. Sometimes, Métis hunting parties included as many as 2,000 people. Métis bison hunting camps were highly organized and were governed in a strict military fashion. The hunt had to be organized because the whole community relied on bison for food. Even prior to the bison’s near decimation in the 1870s, the Métis recognized that the animals were a finite resource that had to be protected. In 1840, the Métis codified the protection of this invaluable resource through The Laws of the Hunt:

- No buffalo to be run on the Sabbath day.

- No party to fork off, lag behind, or go before, without permission.

- No person, or party to run buffalo before the general order.

- Every captain with his men, in turn, to patrol the camp, and keep guard.

- For the first trespass against these laws, the offender to have his saddle and bridle cut up.

- For the second offence, the coat to be taken off the offender’s back, and be cut up.

- For the third offence, the offender to be flogged.

- Any person convicted of theft, even to the value of a sinew, to be brought to the middle of the camp, and the crier to call out his or her name three times, adding the word “Thief,” at each time.

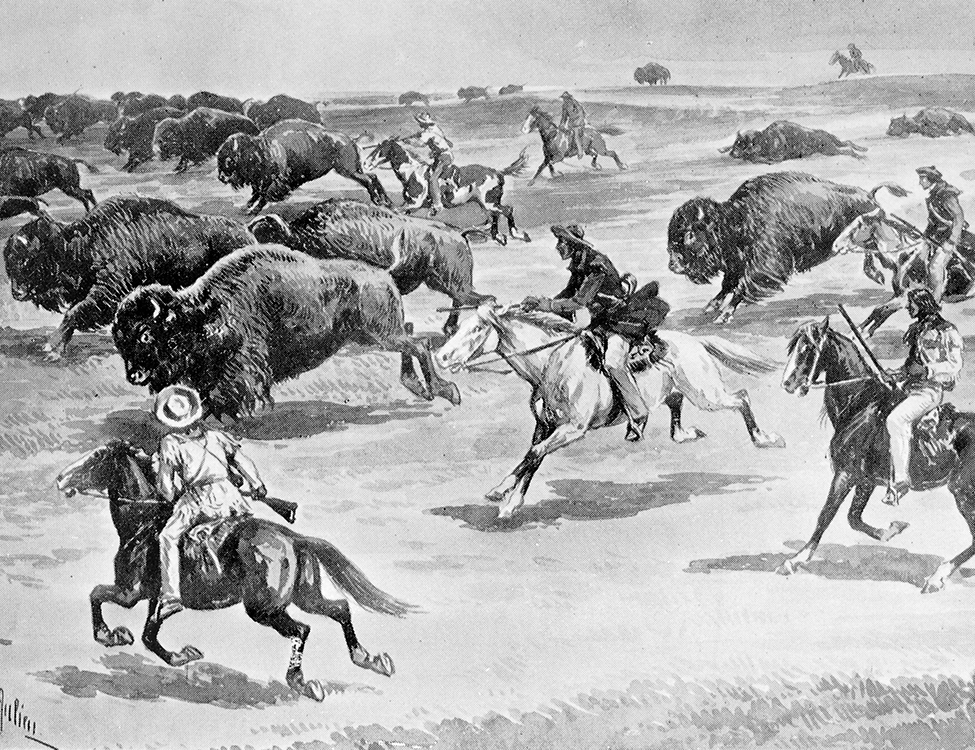

While hunting, Métis bison hunters rode horses known as “buffalo runners.” These swift, powerful horses were trained to run straight and to maintain their speed while the hunters loaded, aimed, and shot their guns. Hunting took a great deal of skill for both the horse and rider, especially when they rode into large, panicked herds of fast-moving bison. For identification purposes, Métis men often left a gauntlet or a mitten by their kill for their wives and other women relatives to find. Métis women were essential to the bison hunts as they processed all the meat and prepared the hides. Led by long-time hunt chief, Gabriel Dumont, the “Society of the Generous Ones” ensured that the meat was shared with all those who couldn’t provide for themselves, such as the elderly and infirm and widows and orphans. The Métis used bison meat, most often made into pemmican, for food and for trade. They also processed bison hides for their leather, which was used to make clothing and for trading purposes. More durable than leather made from cattle, bison leather was used to make industrial belts in the American northeast for much of the nineteenth century.

Overhunting, done largely by non-Indigenous hunters and guided by official American government policy to decimate the bison as a food source for Indigenous peoples, led to the bison’s near extinction. Canadian government policy also exploited the loss of bison as a food source for Indigenous peoples by forcing starving First Nations peoples on to reserves and by withholding food for reserve residents in order to control them.

North American bison (Bison bison) are members of the bovine tribe which also includes cattle and yaks. Historically, these animals have been known as “buffalo,” even though they are only distantly related to true buffalo, such as the Asian water buffalo and the African buffalo. The Michif word for bison, lii buffloo, was used long before people knew these animals’ true taxonomic and genetic history.

Sash / Li sayncheur flayshii

Since the late 1700s, the Métis have worn sashes, and today the sash is considered an integral and highly symbolic aspect of Métis identity. No Métis cultural or political event is considered official until someone arrives proudly wearing a sash. In fact, Métis communities honour the social, cultural, or political contributions of accomplished Métis by awarding them the “Order of the Sash.”

The Métis sash is a very highly symbolic and cherished aspect of Métis identity. As a result, many contemporary Métis have assigned symbolic meaning to its various colours to represent shared Métis values and history. This “colour theory” is a thoroughly modern construct and is not based on the actual history, although it does provide a poignant set of metaphors for the Métis Nation’s values and aspirations.

For the Métis, the sash was more than a decorative piece of clothing. It was used as a rope to pull canoes over portages or to harness heavy loads on the backs of those who unloaded freight canoes and York boats. It could even be used as a dog harness. The Métis used the sashes’ fringed edges as an emergency sewing kit, and the sash could be used to carry personal artifacts, such as medicine, tobacco, a pipe, or a first aid kit. It could also be used as a towel or washcloth and, during winter, it could keep a capote fastened to its wearer.

Today, most sashes are made by machines. The finger-woven sashes are usually of higher quality than the machine woven ones, but are rare and expensive. The art form of sash finger weaving is now being revived among the Métis and is being taught to young people.

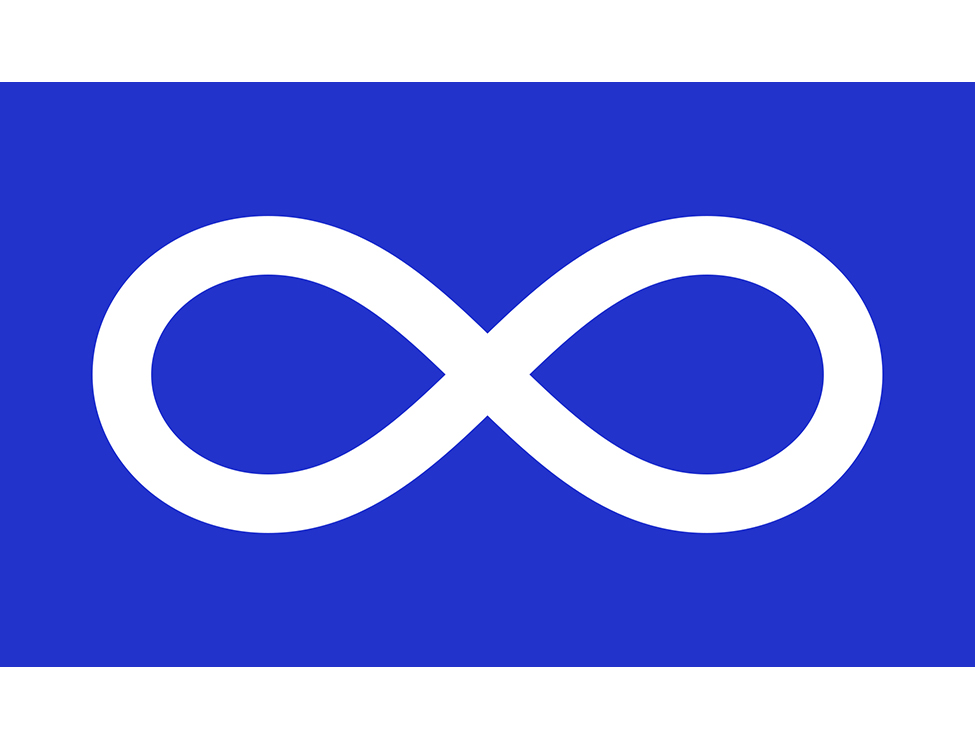

Métis Flag / Li pavillion dii Michif

In 1815, the Métis created the Métis Infinity flag, which as a patriotic symbol predates Canada’s national flag by 150 years! The flag can have either a blue background or a red one and has a white “infinity” symbol emblazoned on its centre. The infinity symbol on the flag was originally described as being a “horizontal circle” or “figure of eight.” In its modern interpretation, the Métis flag symbolizes the fusing of Indigenous and European cultures to form a new and distinct people that will live forever.

In its red variant, the flag was first flown in what is now Saskatchewan’s Qu’Appelle Valley in 1815. On May 31, 1816, just weeks before the Battle of Seven Oaks (June 19, 1816), the Métis flew the blue version of the flag in an engagement against the Hudson’s Bay Company. Traditionally known as “la Grenouillère,” the Battle of Seven Oaks, fought in present-day Winnipeg, Manitoba, is considered as the birth of the Métis Nation.

In the early 1970s, the Association of Métis and Non-Status Indians of Saskatchewan (known as AMNSIS), the forerunner of the Métis Nation—Saskatchewan, brought back the Métis Infinity flag and soon thereafter, Métis across the Homeland began using it as the Métis Nation’s national flag. Both variants of the flag are used: Métis in Alberta prefer the red flag and Métis elsewhere generally prefer the blue one. Today, it is the Métis Nation’s undisputed official flag, although the Métis National Council’s Governing Members, such as the Métis Nation—Saskatchewan or the Manitoba Métis Federation, have their own provincial flags.

Historical Images

Métis with Red River cart.

Library and Archives Canada, C-001517

Métis Traders with members of the North American Boundary Commission, c. 1873.

Library and Archives Canada, e000009381

Gabriel Dumont

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Henri Julien, Grandes Chasses

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Marie Agnes Shortt

Nora Cummings/Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

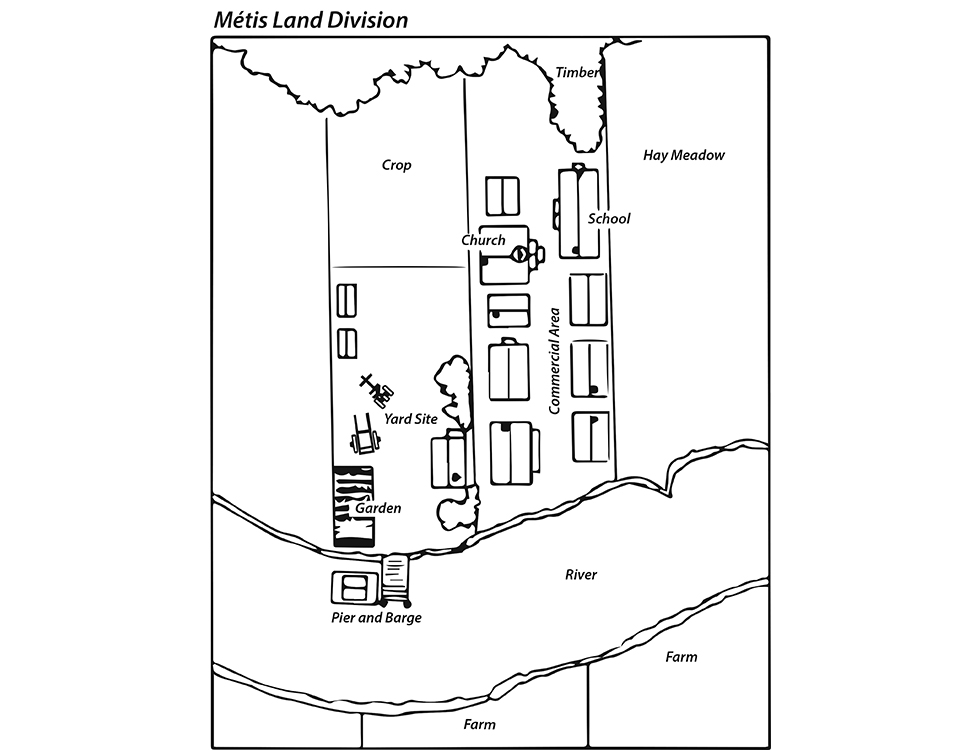

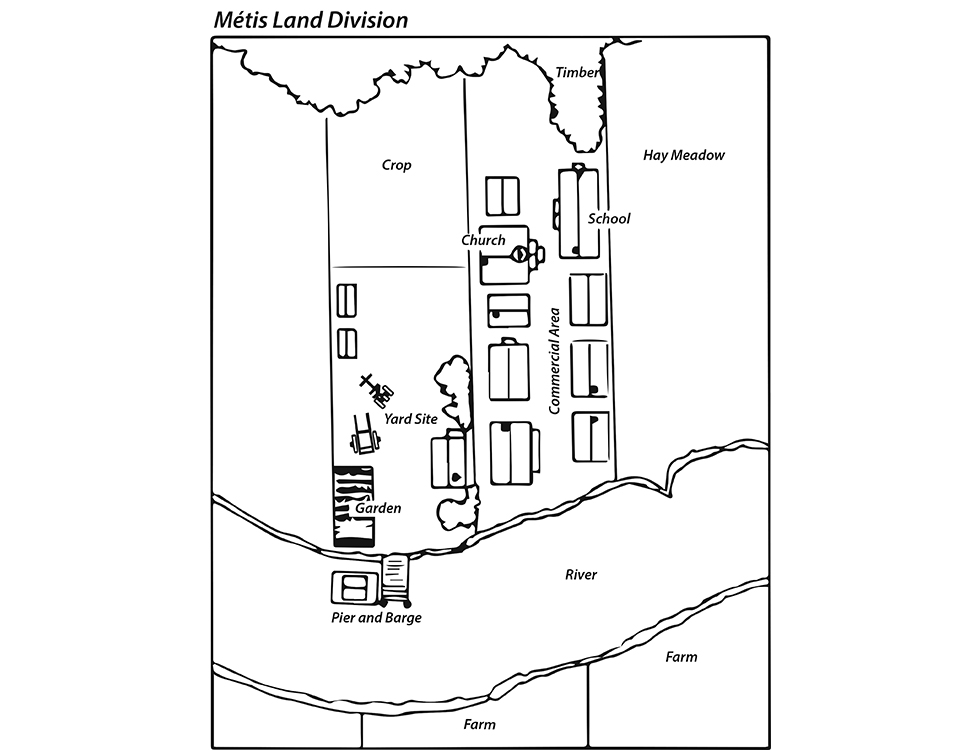

Métis Land Division

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Métis Sash

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Blue Métis Infinity Flag

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Red Métis Infinity Flag

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Red River Cart, Batoche

Image by Peter Beszterda, Gabriel Dumont Institute Archive

Métis Society leaders from the Saskatoon area, c. 1930s

Michael Vandal, Charlie Landrie, Jean Baptiste LaRoque, Alex Fayant, Charlie Oulette William Trotchie Isadore Trotchie, and William Vandale

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

The Historical Distribution of Bison in North America

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Round Prairie

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

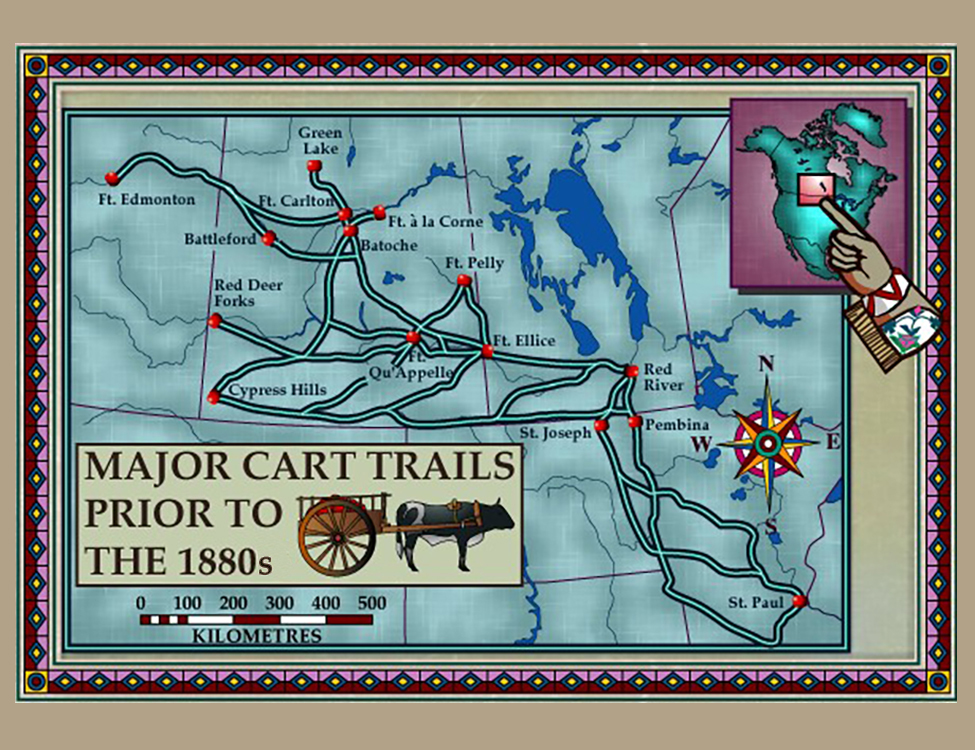

Major Cart Trails Prior to the 1800s

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Métis with Red River cart.

Library and Archives Canada, C-001517

Métis Traders with members of the North American Boundary Commission, c. 1873.

Library and Archives Canada, e000009381

Gabriel Dumont

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Henri Julien, Grandes Chasses

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Marie Agnes Shortt

Nora Cummings/Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Métis Land Division

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Métis Sash

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Blue Métis Infinity Flag

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Red Métis Infinity Flag

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Red River Cart, Batoche

Image by Peter Beszterda, Gabriel Dumont Institute Archive

Métis Society leaders from the Saskatoon area, c. 1930s

Michael Vandal, Charlie Landrie, Jean Baptiste LaRoque, Alex Fayant, Charlie Oulette William Trotchie Isadore Trotchie, and William Vandale

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

The Historical Distribution of Bison in North America

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Round Prairie

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives

Major Cart Trails Prior to the 1800s

Gabriel Dumont Institute Archives